Welcome

The Huffington Post readers - Note: This is Part 2 of an on-going essay. For the Part 1 link with the

La Marquise reference, click

here.

Updated 1/30/12 - Names of passengers for the Paris-to-Rouen race added.

Updated 12/7/11 -

See *Note at bottom of post

As noted in the last

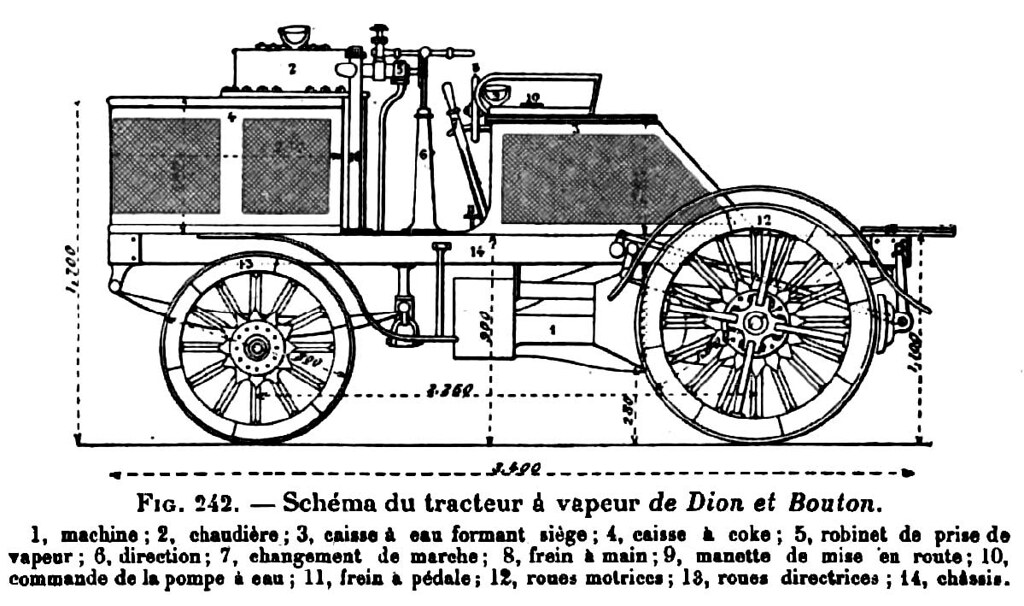

post, the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie received praise throughout the motoring world and remained an engineering discussion topic long after the last one had been retired.

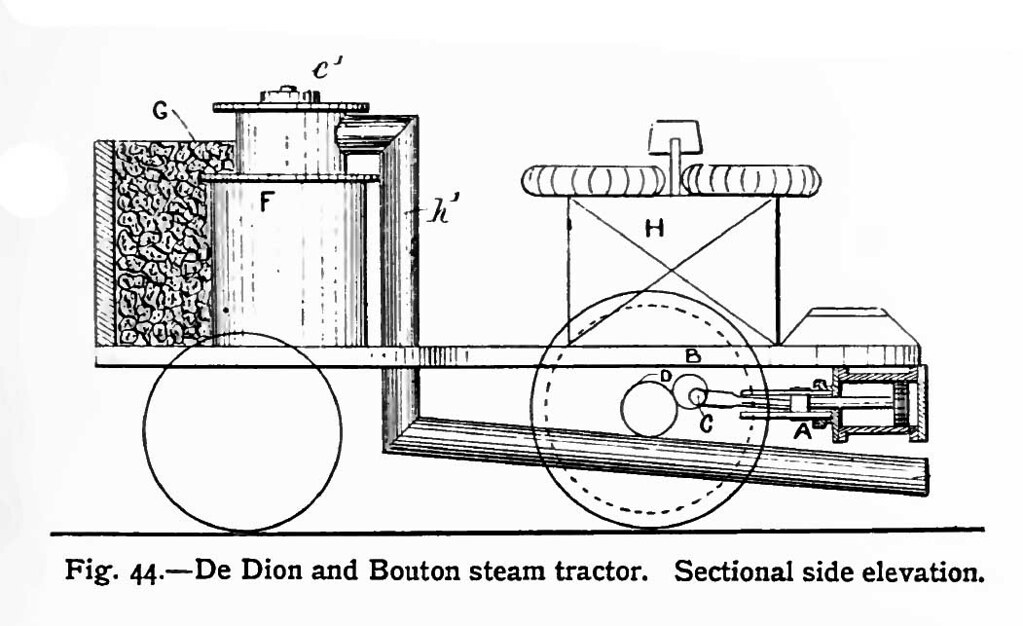

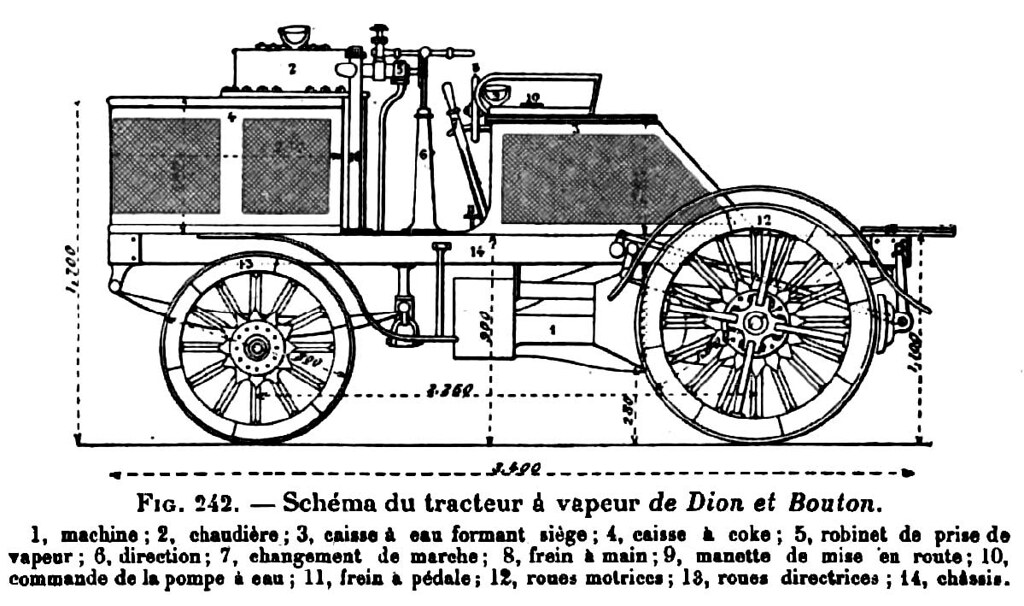

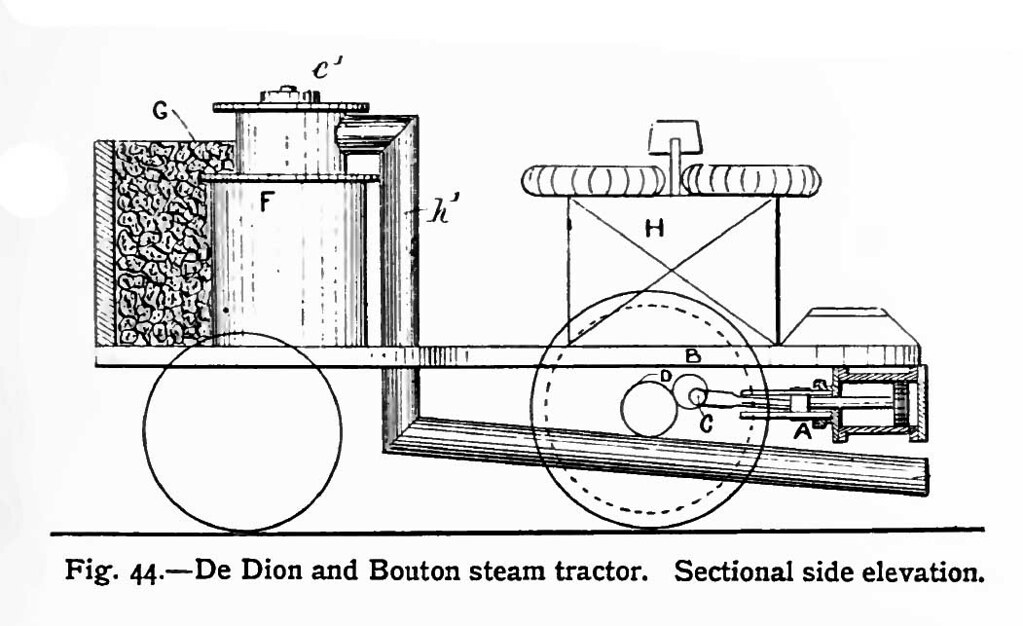

Fig. 242. — Scheme of the De Dion and Bouton steam tractor.

Fig. 242. — Scheme of the De Dion and Bouton steam tractor.

1, Steam engine; 2, boiler; 3, water tank, forming seat; 4, coke (fuel) box 5, steam valve; 6, steering; 7, reversing gear; 8, hand brake; 9, start lever; 10, water circulation pump; 11, brake pedal; 12, driving wheels; 13, steering wheels; 14, chassis.

Illustration from Manuel Théorique et Pratique de L'Automobile Sur Route: Vapeur — Pétrole — Électricité (Theoretical and Practical Manual of the Car on the Road: Steam — Petrol — Electric), Gérard Lavergne, 1900

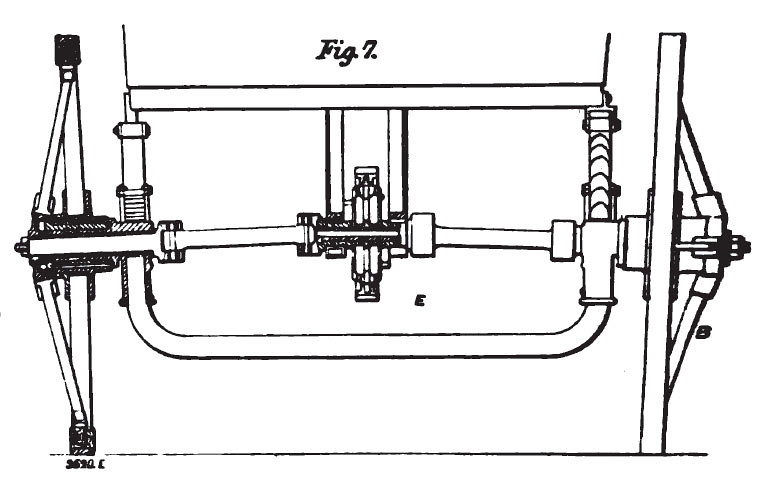

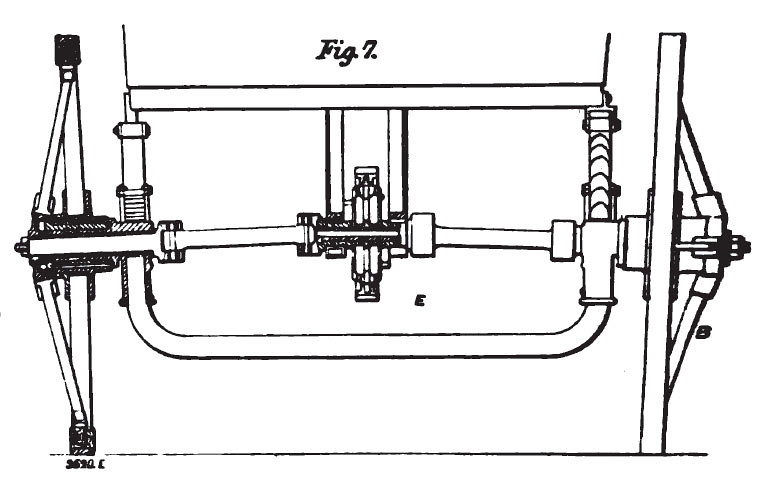

The tractor was the first to use the

de Dion tube suspension or "dead" axle, which only carries weight (below). This suspension system was still in use at least as late as 2004 in AWD Dodge Caravans.

Fig. 7 illustration from the August 14, 1896 issue of Engineering magazine.

Fig. 7 illustration from the August 14, 1896 issue of Engineering magazine.

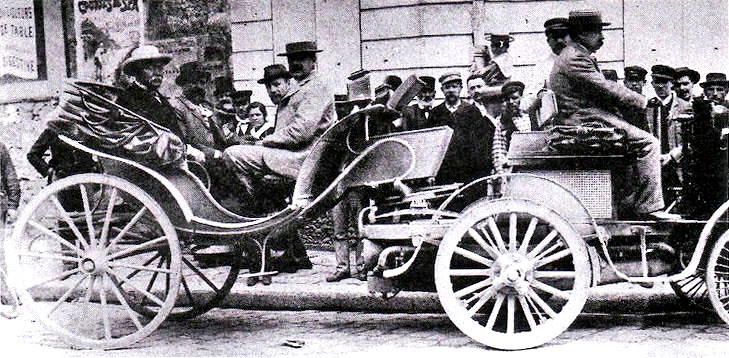

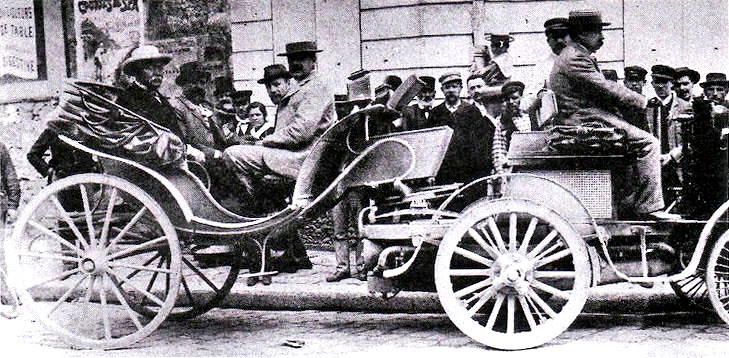

Rare photo taken during the actual 1894 Paris-to-Rouen race. Comte Jules-Albert de Dion (front, right) is driving with his stoker seated to his left. Georges Bouton sits with his back to de Dion, and Bouton's brother-in-law Charles Trépardoux is to his right with his back to the stoker. The other two passengers were Captain Émile Driant and the Baron de Zuylen de Nyevelt. The name of the stoker is unknown to me at this writing. Image from Le Blog de Rouen.

Rare photo taken during the actual 1894 Paris-to-Rouen race. Comte Jules-Albert de Dion (front, right) is driving with his stoker seated to his left. Georges Bouton sits with his back to de Dion, and Bouton's brother-in-law Charles Trépardoux is to his right with his back to the stoker. The other two passengers were Captain Émile Driant and the Baron de Zuylen de Nyevelt. The name of the stoker is unknown to me at this writing. Image from Le Blog de Rouen.

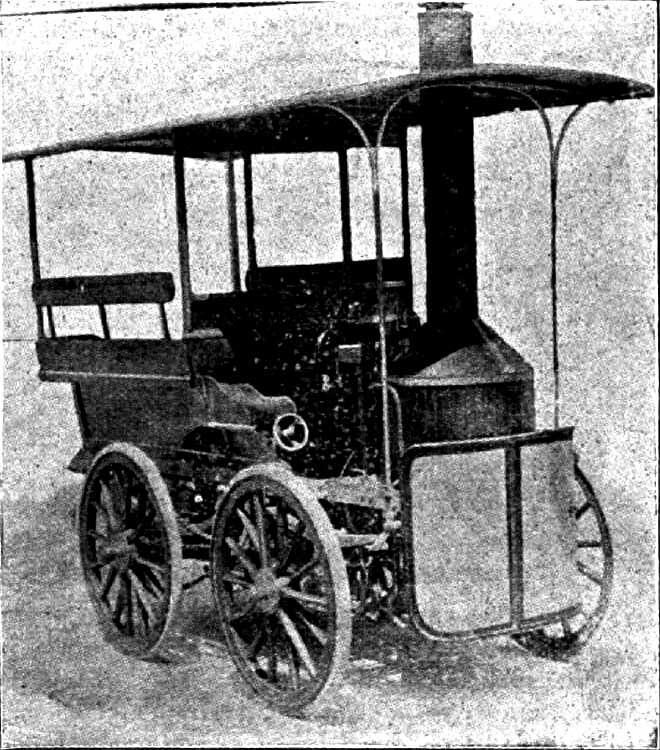

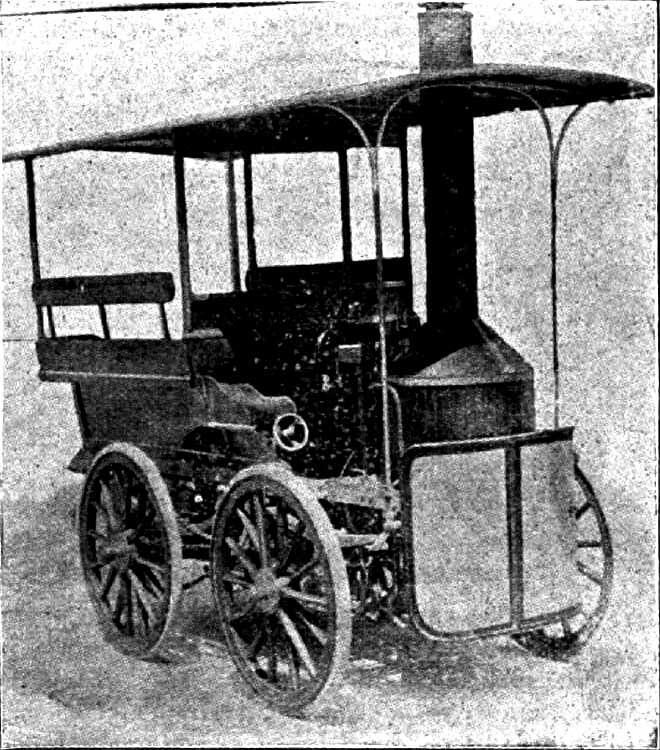

One unique thing about Trépardoux's design of the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie was that the firebox's smokestack was not mounted vertically, as it was on nearly every other steam powered vehicle of the day (including even later De Dion-Bouton vehicles), such as the 1899 Crowden Steam Brake show below:

From the July 26, 1899 issue of The Horseless Age magazine.

From the July 26, 1899 issue of The Horseless Age magazine.

Instead, the stack ran down and to the rear of the steam drag (below). At speed, the draft of the vehicle would suck the exhaust under the trailer and out the back. At idle things could get a bit smokey for the passengers if the stoker didn't keep a clean stack.

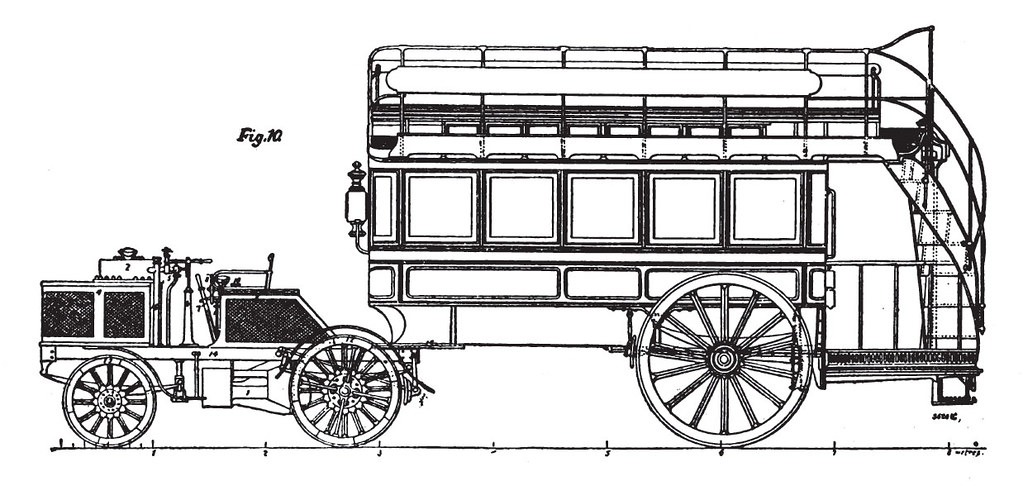

Illustration from Motor Vehicles for Business Purposes: A Practical Handbook for Those Interested in the Transport of Passengers and Goods, A. J. Wallis-Tayler, 1905

Illustration from Motor Vehicles for Business Purposes: A Practical Handbook for Those Interested in the Transport of Passengers and Goods, A. J. Wallis-Tayler, 1905

Not long after the 1894 Paris-to-Rouen race, the Count de Dion led a group of enthusiastic organizers (who later formed the Automobile Club of France, the world's first such organization) in setting up a 732 mile long race — the winner of which would be the first to cross the finish line — to be run from Paris to Bordeaux and back in 1895. De Dion-Bouton entered three vehicles: a Steam Bogie converted into a four-seat brake; a petrol tricycle; and the now famous Steam Bogie/carriage combination that ran the 1894 race. After dominating the early lead, the converted Steam Bogie/brake snapped part of its running gear and was out of the race. Up until then, the 15-horsepower steam brake had been running in first-place at speeds close those at which it had been tested — 30 to 38 miles an hour, making it the unofficially fastest auto of its time. It would be three more years before the first official World Land Speed Record (timed by stop watches) was established. After some modifications and upgrades, the converted Steam Bogie was sold to the Michelin brothers who continued to race it for some time.

The veteran Steam Bogie/carriage combination (below) also ran strong at first, but developed problems and had an excruciatingly slow second half, finishing last and so late that it was declared out of the race. The petrol tricycle finished a surprising third overall (and in no small part helped to contribute to the future direction of the company). In keeping with an apparently nascent tradition, the first vehicle to cross the finish line was disqualified because it only carried two people as opposed to the four carried by the next vehicle to cross the line some twenty minutes later.

Original caption reads: The ancestors of the De Dion-Bouton factory. Steam tractor towing a carriage, comes in first in the Paris-Rouen race (1894). However, this picture is from the 1895 Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race since in the Paris-Rouen contest, only the Count de Dion drove and the Steam Bogie wore the racing number 4. In the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race there were multiple drivers and various contemporary journals referred to it as "No. 1" (note racing number 1 in above photo).

Original caption reads: The ancestors of the De Dion-Bouton factory. Steam tractor towing a carriage, comes in first in the Paris-Rouen race (1894). However, this picture is from the 1895 Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race since in the Paris-Rouen contest, only the Count de Dion drove and the Steam Bogie wore the racing number 4. In the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race there were multiple drivers and various contemporary journals referred to it as "No. 1" (note racing number 1 in above photo).

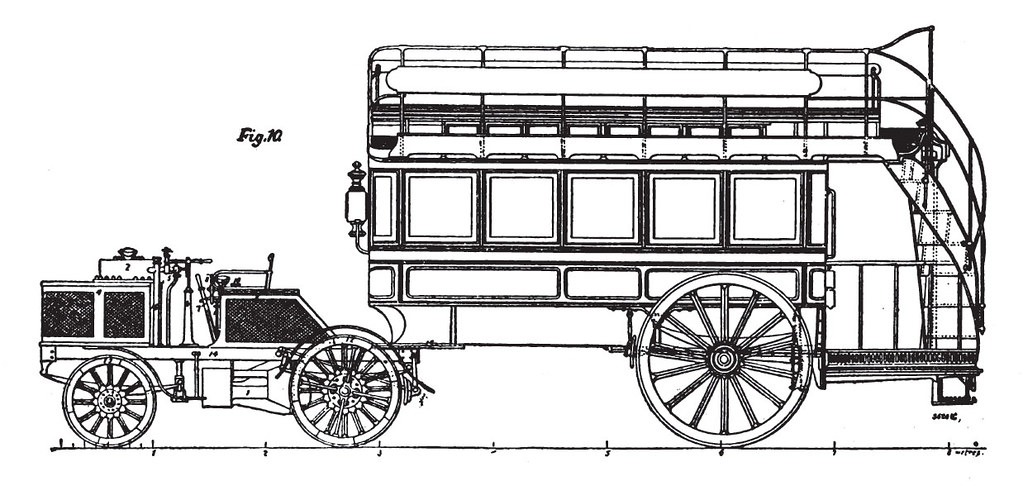

The De Dion-Bouton Company continued their racing and trials efforts with mixed results. In 1896 the next major race sponsored by the newly-formed Automobile Club of France was 300 miles longer (Paris to Marseilles and back), but now broken up into ten stages (five each way) rather than being a marathon. De Dion-Bouton ran the only two steam entries — the other 30 were all petrol powered (which included 5 De Dion-Bouton tricycles — three of which finished, earning De Dion-Bouton a trophy for their motors). They actually started with three steam entries. The venerable Steam Bogie veteran of the 1894 and 1895 contests was scheduled to pull a 40-seat omnibus owned by the Paris Company, which was usually pulled by three horses (drawing below).

From the September 26, 1896 issue of Scientific American Supplement.

From the September 26, 1896 issue of Scientific American Supplement.

For this race Bouton was to drive and the Steam Bogie was to run on large new pneumatic tires for the first time, rather than the usual solid steel tires on the artillery-style wheels. Michelin supplied the tires, but in their haste to get their own entries ready,* the brothers failed to sufficiently study the Bogie, and so did not make a proper fit. The weight of the steam drag ruptured all of the tires before it even got to the staring line, rendering it a non-starter. *One Michelin brother entered a Michelin-built Bollée style Voiturette (a tri-car), while the other brother drove an actual Voiturette Bollée (example below). The Michelin-built No.

39 Bollée came in dead last out of 14 finishers, while his brother finished 5th, but on the No.

51 De Dion-Bouton tricycle! But that, as they say, is another post.

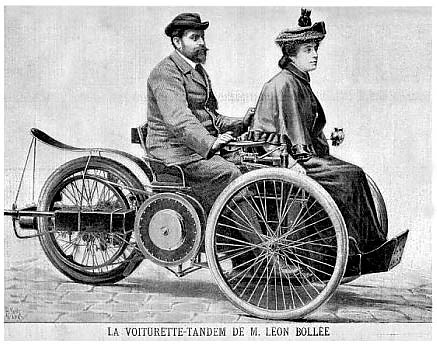

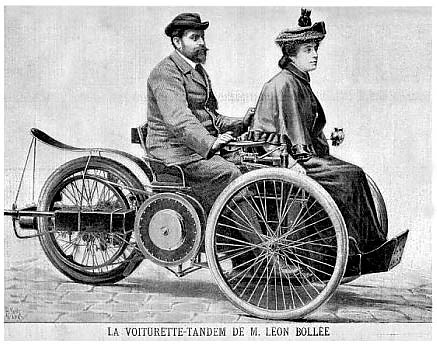

"The tandem small car of Mr. Leon Bollee." A Voiturette Bollée from the May 10, 1896 issue of Le Petit Journal.

"The tandem small car of Mr. Leon Bollee." A Voiturette Bollée from the May 10, 1896 issue of Le Petit Journal.

The other two De Dion-Bouton entries were listed as a Steam Wagon and a Steam Brake. In the 1902 book

Motors and Motor-Driving by Alfred C. Harmsworth, the Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat, who drove one of them, recalled that they were nearly identical and had been special-built just for this race.

Image from the October, 1896 issue of The Horseless Age magazine, which described the De Dion-Bouton No. 12 car as: "Steam wagon conducted by the Count de Dion, and carrying three more persons."

Image from the October, 1896 issue of The Horseless Age magazine, which described the De Dion-Bouton No. 12 car as: "Steam wagon conducted by the Count de Dion, and carrying three more persons."

The Count de Dion's car suffered a hotbox (overheated wheel bearing) and dropped so far back that it was pulled from the race by the second stage. The No.

10 entry driven by the Marquise was described as: "Steam break for six, conducted by MM. the Marquise and the Count de Chasseloup Laubat, and carrying three mechanics." One of the mechanics was actually the fireman (stoker).

The Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat recounted that the No.

10 car (below) was beleaguered with "every break-down conceivable, except for an absolute explosion of the boiler." They spent a total of 47 hours making repairs, which put them far out of contention. However, they decided to continue and finish the race for the "honour of the steam-principle." Alas, it was not to be, as the vehicle broke down for the last time at Lyons. They too, did not even make to the end of the second stage.

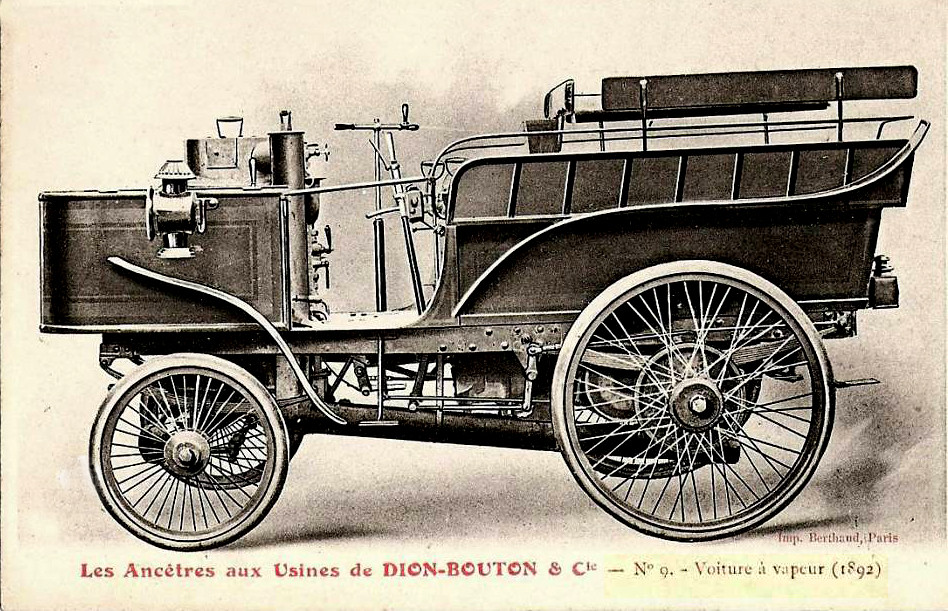

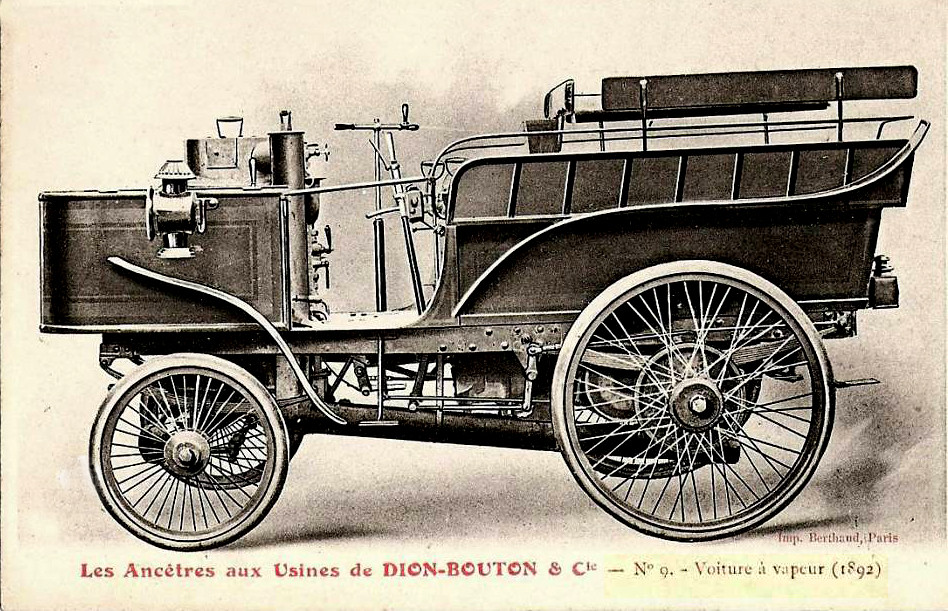

The six-seat De Dion-Bouton No. 10 steam brake as driven by the Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat and his brother the Count de Chasseloup-Laubat. The 1892 date on the later issued commemorative postcard is incorrect, as this particular vehicle was special-built in 1896.

The Horseless Age

The six-seat De Dion-Bouton No. 10 steam brake as driven by the Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat and his brother the Count de Chasseloup-Laubat. The 1892 date on the later issued commemorative postcard is incorrect, as this particular vehicle was special-built in 1896.

The Horseless Age opined that the De Dion-Bouton failures "means the death-blow of steam." They were somewhat premature. Just three months later, after making improvements and modifications, the No.

10 was driven by the Count de Chasseloup Laubat to a decisive victory in the 145 mile Marseilles-to-Monte Carlo race (today known as the Marseilles-Nice-La Turbie race). It averaged a stunning 18.7 miles per hour.

* It would be this same Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat who, on December 18, 1898, would set the world's first official Land Speed Record near Paris at 39.245 mph in a Jeantaud electric vehicle, earning him the sobriquet "The Electric Count." It has been said that this was the first time that a steering wheel was used in place of a steering lever.

*Note - The Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat was remembering his late brother's exploits six years after the fact. The February, 1897 issue of

The Horseless Age reported that the race was 150 miles long, making his average speed 19.35 mph. He ran the final stage at an average of 21 mph.

The De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie was proving to be a hit, especially among the omnibus and coach trade, and the company catered to the industry with new tractor-trailer combinations. We'll take a look at some of those in the next installment.