Part 1 here

Part 2 here

1896 appears to have been the pinnacle year in terms of development of the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie. Most subsequent engineering efforts would be geared towards stand-alone steam omnibuses and trucks, and especially towards gasoline automobiles. But for now the popularity of the Steam Bogie was at an all time high. The Steam Wagon and Steam Brake that were entered in the September, 1896 Paris-Marseilles-Paris race noted in the last post, were essentially converted Steam Bogies. The smaller Steam Wagon that the Count de Dion drove was based on the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie Pattern No. 1, which weighed in at 4,400 lbs., and could haul a 2,640 lb. load at 12.5 mph. The heavier Steam Brake driven by the Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat was based on the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie Pattern No. 2, which weighed 8,800 lbs. and could haul a 22,000 lb. load at 8 mph. Converted to stand-alone vehicles, both were considerably faster without trailers as evidenced by the Count de Chasseloup Laubat’s win with the larger Steam Brake in the late January, 1897 Marseilles-Nice-Monte Carlo race (which, as noted in last post, is today referred to as the Marseille-Nice-La Turbie race), and with De Dion-Bouton’s factory entry in the 106 mile Paris-Dieppe race on July 24, 1897, where the smaller Steam Wagon came in First-in-Class and Second-Overall.

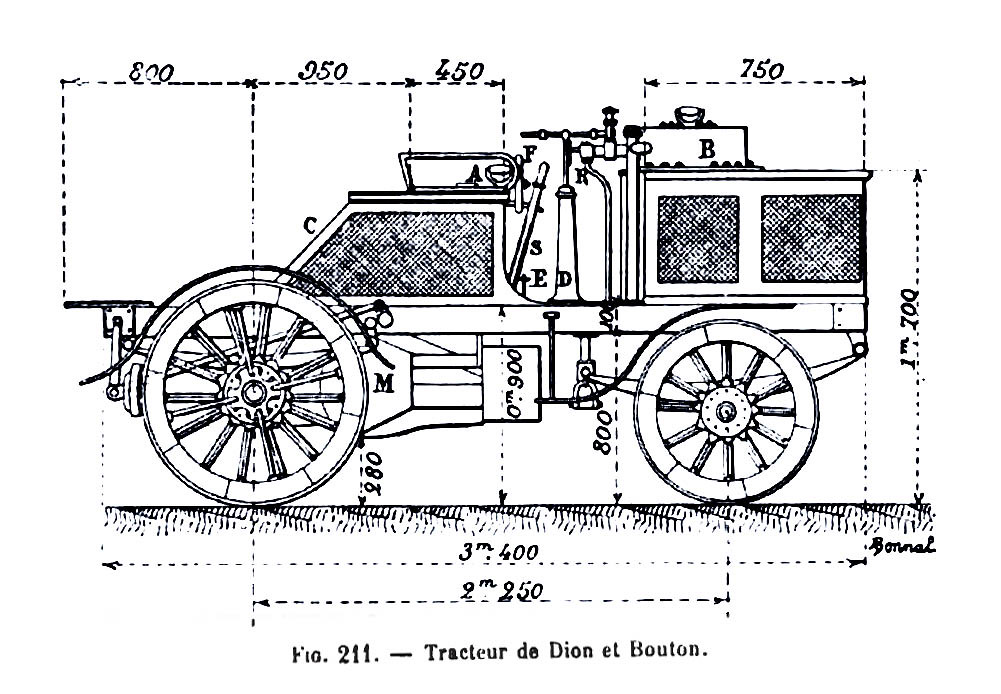

The De Dion-Bouton boiler was smaller than most of its contemporaries, but it was extremely capable. It had a heating surface of 22.76 sq.ft., and a grate area of 1.86 sq.ft. This was sufficient to steam around 6 pounds of water per pound of coke, which was more than enough to power an 18 hp steam engine — a remarkable feat considering that the boiler weighed in at only 528 pounds empty, making it one of the most efficient of its day. The steam fed a compound steam engine (Figs. 35 and 36 below) with a large cylinder that had a diameter of 7.08 inches and a stroke of 5.11 inches. The small cylinder was 4.72 inches. The volume of each individual cylinder was worked out so that each was putting out the same amount of work, which was standard for compound steam engines. Super-heated steam entering the high-pressure small cylinder would power the piston for eight-tenths of its stroke, pushing the engine to a normal working speed of 330 rpm. This translated to the 12.5 mph at 18 hp mentioned above for the Steam Bogie Pattern No. 1. For starting from a dead stop and for help running up grades, a twist of a petcock routed the now-cooler and lower pressure steam from the small cylinder exhaust into the large low pressure cylinder, thereby giving a boost of power. A pinion on the main shaft acted as a differential, allow the wheels to turn at different speeds. They avoided chain drive by employing universal joints which connected the driveshaft to the shafts on the driving wheels.

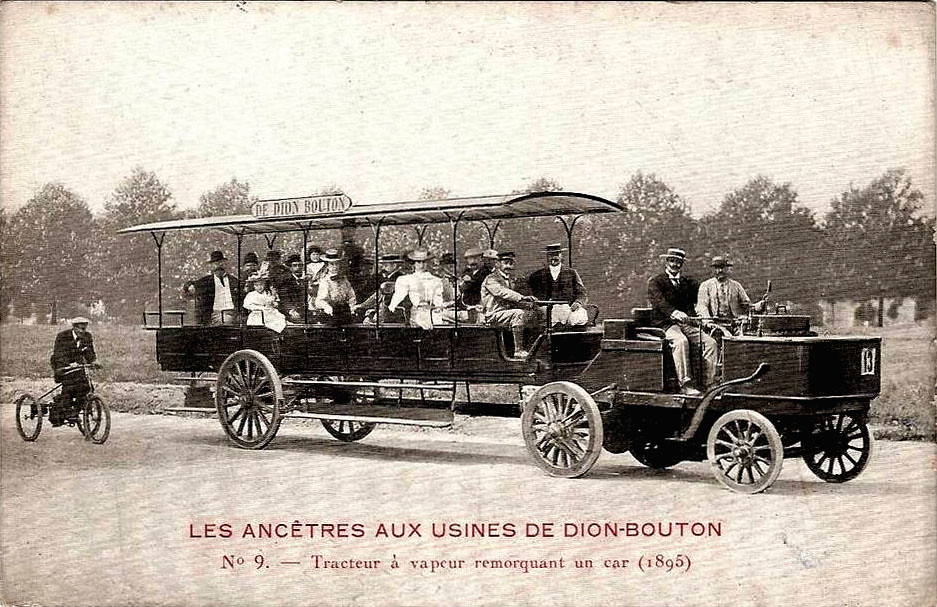

The December, 1896 issue of The Horseless Age reported on the annual Salon du Cycle (Cycle Show) held in the Palace of Industry. In an article titled "Motor Vehicles at the Salon du Cycle," they commented that the show was "more than ever distinguished by its exhibit of motor vehicles of all kinds, a fact which has caused some little feeling of jealousy on the part of the cycle manufacturers, and will doubtless necessitate a separate motor exhibition in the future." In two years the Count de Dion would create the first stand-alone Auto Show, the Salon de l'Automobile. In 1988 the name was changed to Mondial de l'Automobile, which familiarly translates as the Paris Motor Show. At that 1896 Cycle Show, De Dion-Bouton & Co. had the largest display, "showing eighteen petroleum bicycles as well a number of their original steam tricycles." Although they apparently did not show any other steam vehicles, the Steam Bogie was represented as The Horseless Age reported: "The Compagnie Suisse des Voitures Automobiles, 33 Rue du Rone, Geneva Switzerland, show an omnibus drawn by a De Dion steam tractor. The omnibus carries twenty passengers, and is said to give good satisfaction."

Not everyone was completely enamored with the Steam Bogies, however. In Auto-Cars: Cars, Tramcars, and Small Cars, the same-year translation (translated by Lucien Serraillier) of Dick Farman's 1896 Les Automobiles: Voitures, Tramways et Petits Véhicules, Farman comments:

Messrs. de Dion & Bouton have applied their boiler not to auto-cars properly so called, but to tractors or cars for hauling another vehicle. Their apparatus is really a horse—an iron and steel horse—strong, never tiring, but very ugly to look at when coupled to a light and handsome car. It is a hippopotamus drawing a canoe behind it, and in our opinion nothing is so ugly as to see this steam monster puffing and blowing and hauling a coupé or a landau.

We are not criticising the tractor itself, because it is an extremely useful one, but we are criticising its application to pleasure locomotion. It is excellent for the purposes of transport between two places, for the carriage of heavy goods, and for hauling heavy vans, although it cannot, like Mr. Le Blant's tractor, give sudden pulls for the purpose of starting again in difficult places on the road.

These powerful tractors may render good service in hauling heavy leads, such as ammunition waggons, vans, &c., which at present require a large number of horses difficult to manage. How much simpler it would be to use a tractor similar to the above! Not only would it be more simple, but also much more economical, and there would be advantages in adopting it in all respects, but unfortunately routine and force of habit prevent our adopting this new method in one day.

We cannot, however, recommend this tractor for pleasure auto-cars, for reasons already given.

Under the heading "Contest for Heavy Vehicles at Paris," the aforementioned December, 1896 copy of The Horseless Age had the following article positioned immediately after the Salon du Cycle story:

The Race Committee of the Automobile Club has issued the general regulations under which the international contest for heavy vehicles will be held on July 1, 1897.This would be the Concours des Poids Lourds (Heavyweight Truck Contest)—usually referred to as Les Poids Lourds—the competition for large vehicles that was held at Versailles. The categories and finishing entries (with purchase price) were:

The contest will take place somewhere in the neighborhood of Paris, and the competing vehicles will be divided into two general classes—omnibuses and delivery wagons.

Decision will be rendered mainly on the economy shown by the vehicles—that is, the cost of operation as compared with the weight transported.

In the first class competing vehicles must have a capacity of at least 10 passengers, with baggage estimated at about 70 pounds for each passenger.

Vehicles of the second class must have a capacity of at least a ton.

Vehicles intended for the transportation of both passengers and merchandise are required to have a minimum capacity of at least 2,250 pounds.

While any manufacturer will be allowed to enter more than one vehicle, the number of vehicles of the same type which he may enter will be limited.

An entrance fee of 200 francs will be charged for each vehicle, to be paid before June 1.

The lists will close positively on the 25th of June.

Photographs of all vehicles entered, together with prices of same, must be furnished the committee before June 25.

Arrangements for supplies needed during the contest can be made at places designated by the committee, but every vehicle must be capable of making nine miles without renewing supplies.

Six days will be required to complete the test, which will necessitate a total run of 180 miles, divided into six daily stages, or three different routes out and back. The vehicles will be so grouped that each day some will be passing both ways on each route, making frequent stops and carrying different kinds of merchandise.

Representatives of the Automobile Club will accompany the vehicles and make note of various items of cost, time, etc., and report upon them.

Speed will be subordinate, a maximum being set by the committee, which all contestants will be required to obey.

Parks or stopping places will be provided as in the Paris-Marseilles race. Here all competing vehicles will be required to put up for the night, and all repairs must be made in the presence of the representatives of the club.

Medals will be awarded to vehicles which possess the requirements for either class of service, and a complete illustrated report of the test will be published by the club and given the widest circulation.

I. Public Passenger Transport

1. Motor Vehicles

First category: Steam powered

No. 2—Scotte Omnibus; 22,000 ₣

No. 14—De Dion-Bouton Omnibus; 22,000 ₣

Second category: Petrol powered

No. 19—Panhard-Levassor Omnibus; 18,000 ₣

2. Bogie Motor Vehicles

No. 13—De Dion-Bouton Pauline; 26,500 ₣

3. Motor Vehicles towing trailers

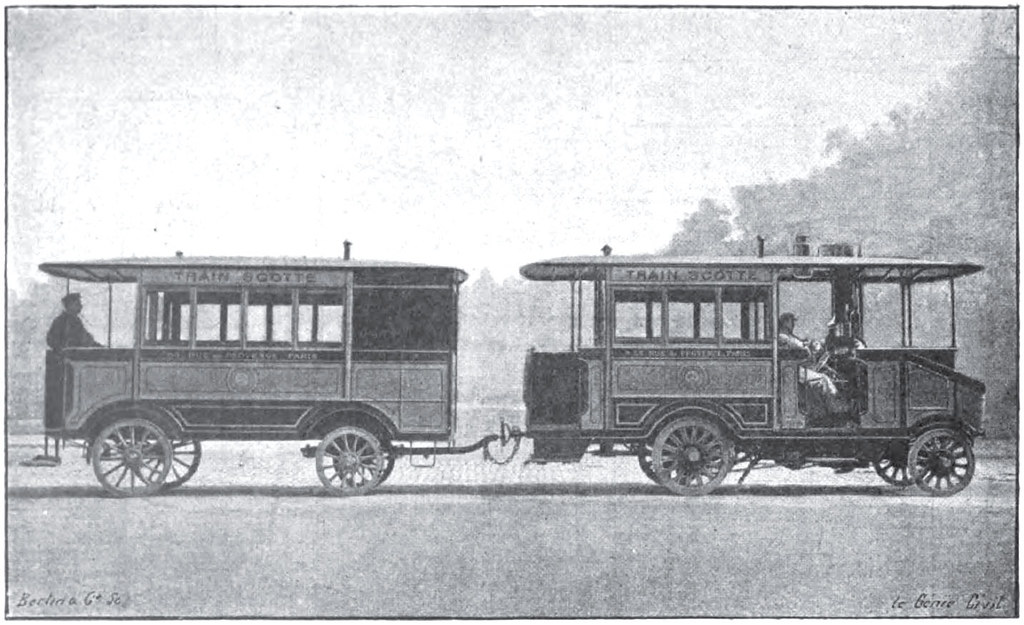

No. 3—Scotte Passenger Train (steam); 26,000 ₣

II. Transport of Goods

1. Motor Vehicles

No. 8—Dietrich truck (petrol); 6,000 ₣

2. Motor vehicles towing trailers

No. 2—Scotte Goods Train (steam); 24,000 ₣

As stated in the rules, the contest was based on economy and not speed. Factoring in the weight carried, the vehicle with the most favorable cost of operation would be the victor. Given the track record (no pun intended) of the previous races, it came as no surprise that things did not work out according to the rules, and that no winner among the seven finishers was declared.

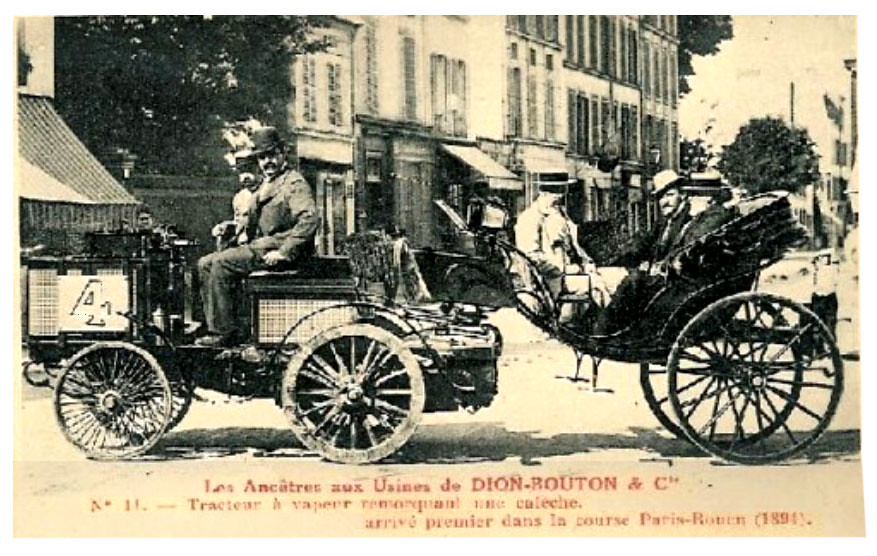

De Dion-Bouton entered two vehicles. The first (No. 13)—a Steam Bogie pulling a heavy pauline (below, with incorrect date on the original commemorative postcard)—was naturally entered in the Public Passenger Transport/Bogie motor vehicles category:

The competition was designed to judge in the areas of reliability, serviceability, maneuverability, degree of comfort, and economy of operation (including the factoring in of the purchase price). According to the August, 1897 issue of The Automotor and Horseless Vehicle Journal:

The principal points to which the Commissioners were to direct their attention and to which they were to give due appreciation were:Still, despite the carefully worded announcement and the detailed list of the things that the Automobile Club or the French Race Committee would be looking at to judge, most entrants misunderstood the intent of the contest, which was to judge each vehicle on the factors mentioned above. Believing that Les Poids Lourds was essentially another speed contest, some manufacturers carried only the minimum allowed weight of cargo or passengers in order to obtain faster times over each course of the trials. Of course, the real objective should have been to reliably carry the most weight or passengers per trip, thereby gaining a higher degree of economy of operation. The misunderstanding of the rules turned the least expensive vehicle to buy into the most expensive one to operate. And, as it turned out, the most expensive vehicle to buy was the least expensive to operate.

Smell and noise of exhaust;

Visibility of exhaust vapour, particularly in the case of steam;

Vibrations;

Ease of suspension;

Noise made by the machine in motion;

Degree of comfort of the vehicle;

Dust and dirt made by working the motor;

Power of the motor, facility of steering;

Change of speeds, whether easily accomplished or not;

Ability to stop and start on inclines;

Necessity or otherwise of going backwards in order to obtain

momentum in mounting an obstacle;

Necessity or otherwise of lightening the vehicle when starting;

Efficiency of brakes for stopping on and descending gradients;

Lubrication;

Proper capacity of [fuel] bunkers and [water] feed tanks;

Seizing of the machinery;

Breakage of any part;

Leakage of steam, feed water, or fuel;

Condition of feed pump;

Pressure gauge, and in oil-motors condition of ignition

apparatus;

Regularity of explosions and feed;

Proper circulation of cooling water;

Supply of oil, how carried.

De Dion-Bouton itself misunderstood the concept of economy of operation when it came to factoring in the purchase price. The 1897 journal Memoirs and Proceedings of the Society of Civil Engineers of France reported that, while De Dion-Bouton’s No. 13 entry cost 26,500 ₣ delivered (17,500 ₣ for the tractor and 9,000 ₣ for the pauline), consideration should be given to the fact that the pauline in the competition was a custom-built luxury vehicle. A pauline built for general revenue service would be at least 4,000 ₣ cheaper, lowering the original purchase price to 22,500 ₣ and making it 3,500 ₣ less expensive than its closest competitor.

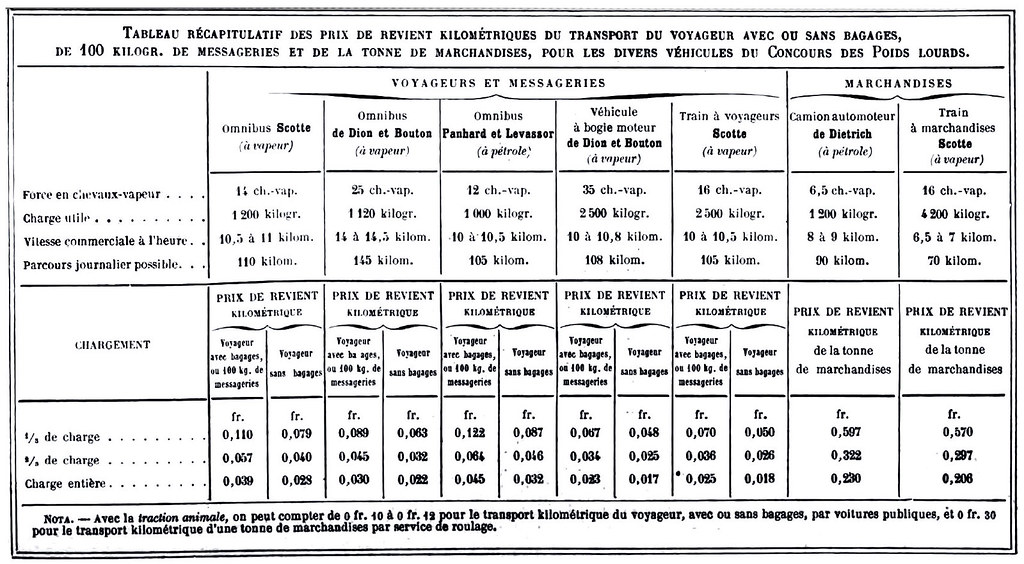

Because of the numerous misunderstandings, the Race Committee decided not to declare an overall winner. Rather, they decided to just publish the results of each competitor’s scoring (below) and let the public sort out which vehicle would suit which industry better.

In the Public Passenger Transport category, De Dion-Bouton’s No. 13 Steam Bogie and pauline swept their six trials with the lowest Cost Per Kilometer with one-third load, two-thirds load, and full load for both the “Travellers with 400 kg. of luggage” and “Travellers without luggage” categories. Purchase price notwithstanding, in terms of cost of operation alone the Steam Bogie/Pauline combination edged out the steam powered Scotte Passenger Train (below) to be the least expensive overall to operate.

The article in Memoirs and Proceedings of the Society of Civil Engineers of France noted that, using the same tractor, the pauline could be swapped out for another vehicle that was of a different shape or size, or for another purpose, and the performance would stay the same as long as the weight remained the same—hinting that the Steam Bogie/trailer combination could have competed and won in all categories.

Ironically, the second vehicle (No. 14) that De Dion-Bouton entered in the Public Passenger Transport category of the Concours des Poids Lourds turned out to be one of two De Dion-Bouton vehicles that would signal the beginning of the end of the Steam Bogie. The new De Dion-Bouton Omnibus was somewhat of a departure for the company, being a stand-alone vehicle (below), rather than a tractor-trailer combination, and it had a more common (and much more efficient) vertical exhaust stack rather than the down-turned stack for which they were noted:

The De Dion-Bouton steam omnibus came in third overall, behind the aforementioned Scotte Passenger Train, and had the distinction of having the highest service speed at 14 to 14.5 km/h, and being able to run the longest daily route of some 145 kilometers. All-in-all, the two De Dion-Bouton vehicles made an impressive showing that was followed up later in the month by the De Dion-Bouton factory win-in-class and second place overall finish—with the Count de Dion himself driving—at the Paris-Dieppe race mentioned at the beginning of this entry. Although it wasn’t possible to know at the time, the Paris-Dieppe race would be the last noteworthy racing victory for the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie or its derivatives. It seems only appropriate that the Count, who won that first contest in 1894, was driving for the last triumph in 1897. In the meantime, the second—and far more significant—vehicle to help bring about the demise of the Steam Bogie was being developed by the De Dion-Bouton factory.

Next installment: The End of the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie - Going out in Style.