Updated 12/09/2019*

While researching the material for the De Dion segment of the Land Tug series, I found numerous mentions to "the very first auto race." Often the source would then mention an earlier race. Well, if there was an earlier race, wouldn't that one be the first? As we will see, no. But as it turns out, the first still wasn't the first either, so let's look at race claims, counter-claims, and the perils of internet research.

Just this summer many of us learned that what we thought was the first ever auto race, turned out to be the second (or third) by about 16 years or so. Daniel Strohl of Hemmings Blog fame has written an excellent summary of the Great Green Bay-to-Madison Steam Wagon Race of 1878, while the website for the Wisconsin Historical Society relates how the story was "rediscovered." The original essay by Wisconsin Secretary of State John S. Donald appeared in the October, 1916 issue of The Wisconsin Engineer.

Most histories state that the Le Petit Journal sponsored Paris-to-Rouen race in France on July 22, 1894 was the very first. Given the Steam Wagon Race of 1878, it would properly be the second. However, there had been an earlier race of sorts in 1887, but the information available on the internet is woefully lacking. If you Google "first auto race" you will eventually come across a reference to the April 28, 1887 race sponsored by the magazine Le Vélocipède and its editor, a certain Monsieur 'Fossier.' Google "'Le Vélocipède' Fossier" and you will get over 6,800 entries that all state something very much along the lines of:

The first race ever organized was on April 28, 1887 by the chief editor of Paris publication Le Vélocipède, Monsieur Fossier. It ran 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from Neuilly Bridge to the Bois de Boulogne. It was won by Georges Bouton of the De Dion-Bouton Company, in a car he had constructed with Albert, the Comte de Dion, but as he was the only competitor to show up it is rather difficult to call it a race.

As it turns out, they are all copying a Wikipedia entry almost to the letter. And that is my pet peeve - website after website blindly copying and pasting erroneous information, and thus making the incorrect story the new truth. See the Locomobile entry for another example.

In turn, Wikipedia cites a May 28, 2003 entry by Rémi Paolozzi on the Autosport.com 8W forum. (8W stands for Who? What? Where? When? Why? on the World Wide Web - The stories behind auto racing facts and fiction.) There Paolozzi takes 1 (out of 10) paragraph to tell the story - without citation - that Wikipedia condensed down to a few lines that thousands would copy without citation. Caveat - never, ever trust what you read on Wikipedia. Using it as a starting point for research is fine, but try to trace anything you read back to the primary source. So far I haven't found any earlier examples of the story than this...in English.

The big problem here is that when you read the English Wiki entry for Le Vélocipède, you find that it is properly titled Le Vélocipède Illustré, and that Richard Lesclide was its editor, and that it folded in 1872 - some 15 years before the race. No amount of tweaking search parameters reconciled the disparity. At least, until I switched to Google.fr - the French version. Then the clouds parted and the sun shown down upon my darkened disposition. And no, I don't speak/read/write French, but I can fling Google Translator around with the best of them.

First, there is no Monsieur Fossier. There is, however, according to the French version of the Wikipedia entry for Le Vélocipède Illustré, a Paul Faussier who was a sports journalist, a ranked cycle racer, and a member of the Metropolitan Vélocipédique Company. And he did indeed organize what was supposed to be the first horseless carriage race between Neuilly and Versailles on April 28, 1887. [Source - Les Défricheurs de la Presse Sportive (The Pioneers of the Sports Press) by Jacques Marchand, Atlantica, 1999.] As for the discrepancy concerning the demise of the journal Le Vélocipède Illustré - it turns out that the magazine had a second life.

According to the French Wikipedia site, Richard Lesclide launched the first issue of the journal in Paris on April 1, 1869 as an illustrated bimonthly specializing in the new sport of cycling. Lesclide was a pioneer of sports journalism who would one day be secretary to Victor Hugo. Le Vélocipède Illustré organized the first city-to-city cycle race in history on November 7, 1869, between Paris and Rouen, which would be the same route used 25 years later for the first real auto race in Europe. As noted above, the magazine folded in 1872, but was resurrected in 1890 by the now 67 year-old Lesclide. After he died in 1892, his wife Juana acted as editor under the nom de plume Jean de Champeaux. Sometime later Paul Faussier took over as editor and apparently continued until the journal folded for good around 1901. So Faussier (and not Fossier) was indeed the editor of Le Vélocipède Illustré, but not during the the time of the 1887 auto non-race - which he did indeed organize. [Source - Les Premiers Temps des Véloce-Clubs: Apparition et Diffusion du Cyclisme Associatif Français Entre 1867 et 1914 (The Early Days of Swift-Clubs: Emergence and Spread of French Cycling Associations Between 1867 and 1914) by Alex Poyer, L'Harmattan, 2003.]

So what does all of this mean? Simply that, until someone's future research uncovers an earlier event, the record stands thusly: The first documented self-propelled auto race in the world took place in Wisconsin in 1878 (two entries/one finisher). The 1887 event that some claim is the first race was not a race (one entry/one finisher). What was thought to be the world's first race was actually the world's second, but still Europe's first (multiple entries/multiple finishers). What was thought to be the first American auto race in November, 1895 (multiple entries/multiple finishers) was actually the second American race - 17 years after the Wisconsin race of July, 1878.

Given the early flurry of steam propulsion activity in England (see previous post) I'm betting that if any evidence surfaces for an earlier race, it will be there.

*Hemmings notes (scroll down) that "one of the selling points for “La Marquise,” the world’s oldest operating vehicle, was the claim that it participated in the world’s first automobile race, though...that claim is dubious, considering that the race took place many years after the 1878 Wisconsin steam buggy race we wrote about back in June."

Considering that the 1887 event was only had one entry, it was more properly a time-trial, rather than a race. That makes the claim that the “La Marquise” participated in the world's first automobile race doubly dubious. That said, if the new owner feels cheated and no longer interested in the vehicle, I'd graciously accept it as a lovely parting gift.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Land Tugs Part 1: The Gurney Steam Drag

It's the late 1800s/early 1900s and you are a farmer/merchant/fireman or the like, and you are convinced that it is time to switch from horses to motorized vehicles. The only problem is, you have a very heavy investment in horse-drawn wagons and other equipment. What are your options? With common farm wagons or buggies, you could pretty much get the same thing with a motor attached in the form of a truck or runabout, respectively. Specialized farm or fire equipment, however, was a different matter. Replacing a relatively new horse-drawn steam pumper could be ruinously expensive.

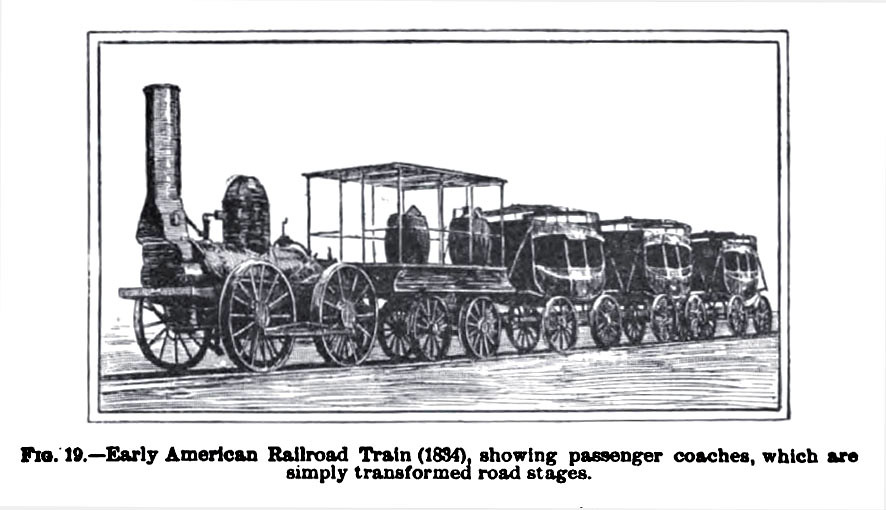

A neat solution was a tractor made specifically for the purpose of motorizing horse drawn vehicles. These were designed to replace the front running gear by either permanently attaching to the equipment (thus creating a semi-new one-piece vehicle), or designed to fit to a number of rigs, and so making a tractor-trailer combination. The idea wasn't new – the first railroad locomotives pulled modified stagecoaches. In fact, an early example of a road-going combination tractor-trailer was in commercial service on rural roads in England even before the first American chartered railroad, the Mohawk & Hudson (absorbed by the New York Central in 1853), launched service with their locomotive, the DeWitt Clinton, in 1831 (shown below).

Illustration of the DeWitt Clinton from Self-Propelled Vehicles: A Practical Treatise on the Theory, Construction, Operation, Care and Management of All Forms of Automobiles by James E. Homans, A.M., Theo. Audel & Company, 1902.

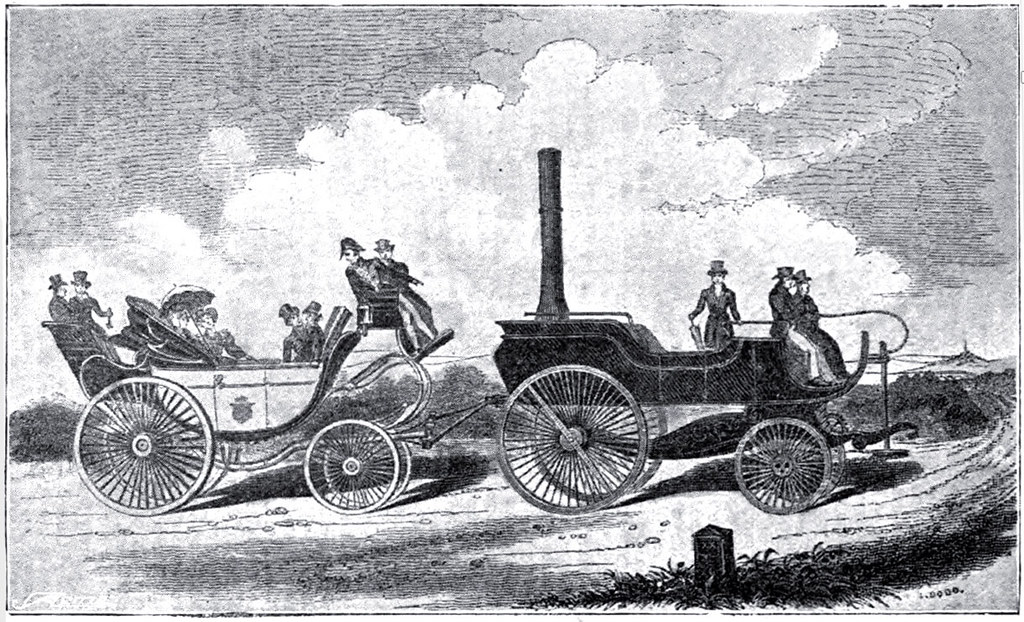

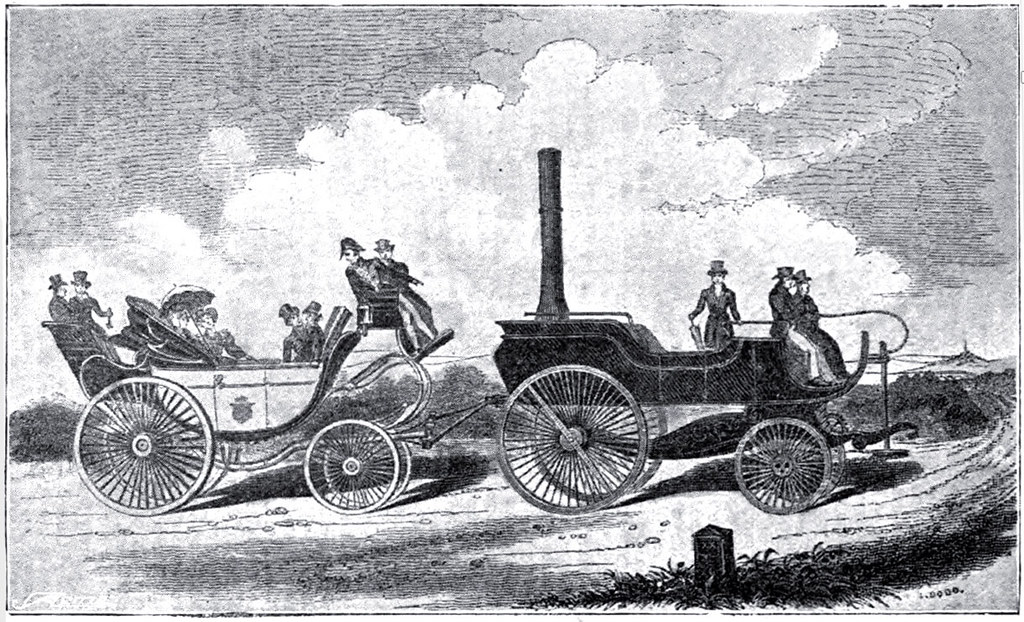

In 1829 Sir Goldsworthy Gurney was experimenting with self-propelled steam carriages. In response to passenger anxiety over riding on top of a potentially explosive boiler, he soon switched to the tractor-trailer system, using a passenger carriage pulled by a separate steam carriage (below).

Illustration from Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History by Henry Charles Moore, Chapman & Hall, 1902.

Dubbed the ‘Gurney Steam Drag,’ two of these were shipped to Glasgow in 1830, where one was eventually tested in service (the boiler on the other exploded when unauthorized persons steamed it up in Gurney’s absence). Soon contractors were buying Gurney steam drags to put in commercial service. Among them, Sir Charles Dance purchased three for rotating service on a Cheltenham-to-Gloucester route, making four runs a day. Unfortunately for the endeavor, jealous owners in the horse-coach trade got Parliament to impose a £2 levy steam carriages per trip, while the toll for horse-drawn carriages remained at 2 shillings. Over 50 other bills placing excessive tolls on steam-carriages were passed in 1831, which eventually shut down the steam-carriage industry throughout England. However, this did not end Sir Charles’ business venture, so devious Cheltenham magistrates clandestinely covered a long section of the road with a foot deep layer of loose gravel, which brought the steam-carriages – and Sir Charles’ business – grinding to a halt.

Sir Goldsworthy Gurney kept his factory open as long as possible, but the withdrawal of contractors coupled with bad press from the Glasgow explosion teamed to bankrupt Gurney, who suffered a £232,000 loss despite selling off his inventory and tools.

See the Wikipedia entry for more info on Sir Goldsworthy Gurney and his inventions.

Next: The De Dion Bouton Steam Bogie

A neat solution was a tractor made specifically for the purpose of motorizing horse drawn vehicles. These were designed to replace the front running gear by either permanently attaching to the equipment (thus creating a semi-new one-piece vehicle), or designed to fit to a number of rigs, and so making a tractor-trailer combination. The idea wasn't new – the first railroad locomotives pulled modified stagecoaches. In fact, an early example of a road-going combination tractor-trailer was in commercial service on rural roads in England even before the first American chartered railroad, the Mohawk & Hudson (absorbed by the New York Central in 1853), launched service with their locomotive, the DeWitt Clinton, in 1831 (shown below).

In 1829 Sir Goldsworthy Gurney was experimenting with self-propelled steam carriages. In response to passenger anxiety over riding on top of a potentially explosive boiler, he soon switched to the tractor-trailer system, using a passenger carriage pulled by a separate steam carriage (below).

Dubbed the ‘Gurney Steam Drag,’ two of these were shipped to Glasgow in 1830, where one was eventually tested in service (the boiler on the other exploded when unauthorized persons steamed it up in Gurney’s absence). Soon contractors were buying Gurney steam drags to put in commercial service. Among them, Sir Charles Dance purchased three for rotating service on a Cheltenham-to-Gloucester route, making four runs a day. Unfortunately for the endeavor, jealous owners in the horse-coach trade got Parliament to impose a £2 levy steam carriages per trip, while the toll for horse-drawn carriages remained at 2 shillings. Over 50 other bills placing excessive tolls on steam-carriages were passed in 1831, which eventually shut down the steam-carriage industry throughout England. However, this did not end Sir Charles’ business venture, so devious Cheltenham magistrates clandestinely covered a long section of the road with a foot deep layer of loose gravel, which brought the steam-carriages – and Sir Charles’ business – grinding to a halt.

Sir Goldsworthy Gurney kept his factory open as long as possible, but the withdrawal of contractors coupled with bad press from the Glasgow explosion teamed to bankrupt Gurney, who suffered a £232,000 loss despite selling off his inventory and tools.

See the Wikipedia entry for more info on Sir Goldsworthy Gurney and his inventions.

Next: The De Dion Bouton Steam Bogie

Sunday, October 02, 2011

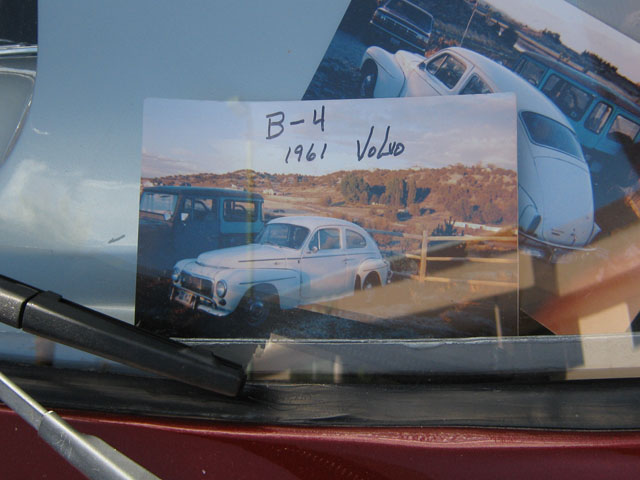

Last Weekend's Car Show in Henderson, NV

I normally leave the car show postings to Just a Car Guy, where Jesse's photography skills are vastly superior to mine (seriously - the guy wins awards for his blog), but since there has been a dearth of posts here lately due to infernal machine problems, I felt that I should get something up. So here's my first car show post (all pictures in this post by me).

It was held September 23 - 25, 2011.

My wife doesn't share my affinity for 1959-60 El Caminos, otherwise one would be sitting in my driveway. I particularly like the 1959 version, so naturally these two are from 1960.

I detect a theme with these four, even though the closest ocean beach is a good five hour drive away.

I didn't notice the images in the flames at first.

The motif is continued under the hood via engraving.

What's this? A VW Bug with a gas tank in the engine compartment?

And what's that in the luggage compartment?

A Chevy four cylinder.

A nice Squarebird.

This Roundbird was customized into a true roadster - no windows except for the windshield.

I didn't expect to see this - it took me back to when I spent most of the late '70s behind the wheel of a '72 Commando.

Nice touch.

The most customized Willys I've ever seen.

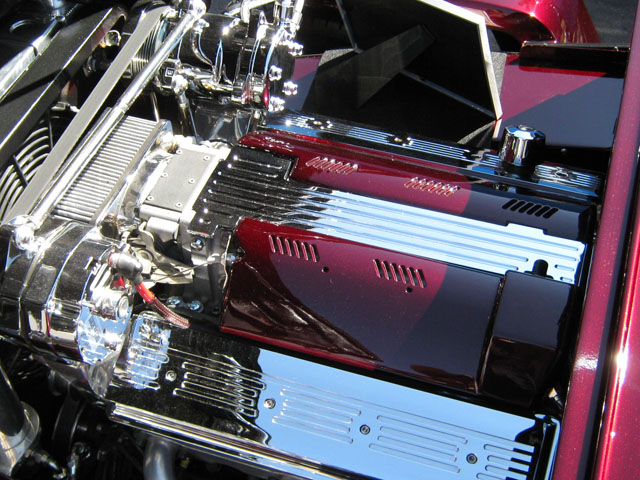

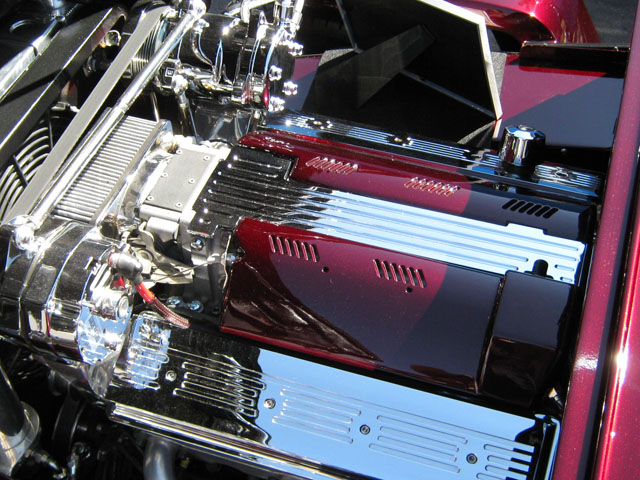

The Willy's engine...

...and bed

Cute restoration by a member of a local lowrider club.

Now I know how I'm getting around when these knees finally give out.

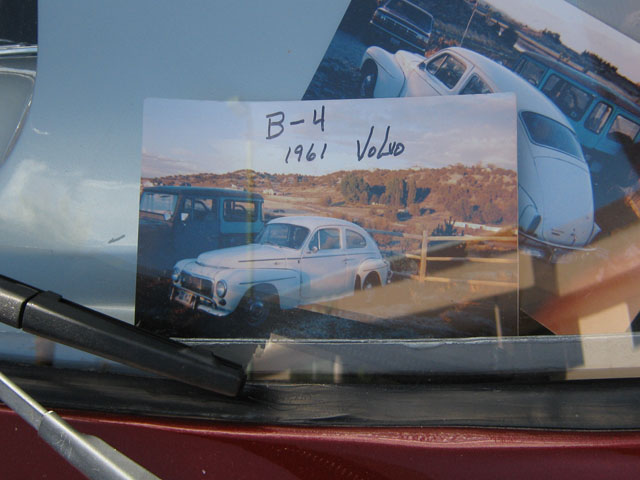

Mostly unrestored. Maybe we should give it to...

...these guys. The restoration company on the History Channel's American Restoration.

That's the owner's (Rick Dale) son Tyler Dale, being teased by his uncle Ron Dale.

I also have a softspot for '50s GM station wagons. This Buick was particularly nice.

This had a modern Toyota engine in it.

When was the last time you saw a Matador this clean outside of an Adam-12 rerun?

In 1969 my sister was given a beige Chrysler version of this to drive to school. She was too embarrassed to drive it and it was swapped for a gold 4-door 1963 Studebaker Lark, with a Rambler engine. Sure would like to have that Chrysler today.

I was a freshman in high school when I saw my first one of these - driven by a cheerleader no less (alas, Chris North was a senior). I always thought that someone should customize one and here 42 years later someone did.

Did you guess correctly?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)